Discover Canada and Explore the Fossils and Geodiversity of Stonehammer UNESCO Global Geopark

- Sep 23, 2025

- 8 min read

Sip back and discover Canada and explore the fossils and geodiversity of Stonehammer UNESCO Global Geopark. Covering an area of 2,500 km² of southern New Brunswick, following the Bay of Fundy coastline and the Saint John and Kennebecasis rivers the geopark preserves a near-continuous rock and fossil record from the Precambrian to the Triassic periods. The Late Precambrian stromatolitic marbles on Green Head and Dominion Park tell a story of ancient microbial life, while the Cambrian–Ordovician Saint John Group beds yield large trilobites such as Paradoxides regina. The Silurian Kingston Group of volcaniclastic rocks hold sedimentary lenses of preserved brachiopod communities, eurypterids and early fishes, and the Devonian red beds of the Kennebecasis Formation show river systems and emergence of lobe-finned fishes like Holoptychius. The Albert Formation’s fossil forest near Norton and the Lancaster Formation’s Fern Ledges of Saint John reveal Pennsylvanian forests and diverse plant and invertebrate assemblages while the Permian–Triassic rock along the Fundy coast, including Hopewell Rocks and the Quaco Formation preserve rift-valley sediments and rare trace fossils of tetrapod tracks. The Stonehammer UNESCO Global Geopark is where visitors can journey through more than a billion years of Earth history, exploring fossils that trace life’s evolution from Precambrian stromatolites to trilobites, early fish, fossil forests, and rare Permian–Triassic footprints along the Bay of Fundy.

Stonehammer UNESCO Global Geopark spreads across 2,500 Km2 a wide swath of southern New Brunswick following the dramatic Bay of Fundy coastline and extending inland along the Saint John and Kennebecasis rivers. In New Brunswick, fossils are legally protected under the Heritage Conservation Act, and collecting them requires a permit. Many of Stonehammer’s notable geological sites are within parks and visitors are encouraged to leave fossils in place, document their location, and report them to the New Brunswick Museum ensuring their the scientific and heritage value for future generations.

In 1838, Dr. Abraham Gesner (1797-1864) originally from Nova Scotia and today is attributed to as “Father of the Modern Petroleum Industry” became the first Provincial Geologist publishing reports that revealed the geodiversity of New Brunswick and even established the Museum of Natural History in Saint John. Widely regarded as the forerunner of the New Brunswick Museum, its original collection now forms the foundation of the institution’s holdings. By 1857, a group of young enthusiasts formed the Steinhammer Club, using Gesner’s work to go on to found the Natural History Society of New Brunswick.

Some of Stonehammer’s most remarkable rocks belong to the Precambrian a time that spans much of Earth’s history beginning with the planet’s formation around 4.5 billion years ago and continues until the appearance of complex and multicellular life with microbial communities called stromatolites that thrived in shallow seas.

Stromatolites are among the oldest known fossils on Earth dating back more than three billion years and they provide crucial insights into early life and the planet’s transformation. Formed by cyanobacteria, a tiny photosynthetic organisms, these dome-shaped, layered structures form through a process of microbial mat growth, sediment trapping, layer accumulation and eventual cementation into solid rock. The oxygen generated by these microorganisms gradually enriched Earth’s atmosphere paving the way for complex life to emerge.

The oldest rocks in the Stonehammer UNESCO Global Geopark are found on Green Head Island and at Dominion Park and are dominated by the Late Precambrian Green Head Group Formations especially the Ashburn Formation composed of stromatolitic marble overlaid by the Martinon Formation.

The Ashburn Formation is described as a metacarbonate in that as shallow marine limestone it has been transformed by heat and pressure through metamorphism to form marble. Dating from approximately 1.2 billion - 750 million years ago its most notable feature is the presence of stromatolites. These areas are particularly known for the stromatolite fossils of Archaeozoon acadiense first described in 1890 by geologist George Matthew the founding member of the Steinhammer Club. It became the first recognised Precambrian stromatolite in scientific literature placing Saint John at the forefront of early palaeontology.

Fast forward to the Cambrian Period about 541 million years ago this was a time of the “Cambrian Explosion” when animals diversified rapidly in the oceans. In the rocks of Saint John’s Cambrian - Ordovician Saint John Group the fossil record holds assemblages of trilobites an extinct marine arthropod. Their hard exoskeletons allowed for exceptional fossil preservation making them a key to understanding early evolution and the emergence of diverse body plans. Trilobites rapidly diversified playing important roles in marine ecosystems as both predators and prey. George Matthew and his colleagues first described Cambrian trilobites here in the 1860s including the large Paradoxides regina.

By the Silurian Period about 430 million years ago the Iapetus Ocean that had once separated North America from Europe and Africa was now closing. The complete disappearance of the ocean occurred by the end of the Silurian Period marked by the continental collision of the cratons of Laurentia, Baltica, and Avalonia forming the supercontinent Laurasia and incidentally laid the foundation for the modern British Isles. This process occurred over millions of years involving the formation of volcanic island arcs and mountain-building events such as the Taconic, Grampian and Scandian orogeny's.

Brundage Point, on the Kingston Peninsula sits atop Silurian volcanic rocks known as the Kingston Group of the fault-bounded Kingston Terrane. Fossils in the Kingston Terrane though limited by the presence of the Early Silurian volcanic and intrusive Kingston Group do occur where sedimentary lenses have formed to preserve marine life.

The Waweig Formation yields diverse late Silurian invertebrate assemblages including a group of fossils of predominantly brachiopods known as a Salopina community that once lived in a quiet, shallow, nearshore shelf or low intertidal environment.

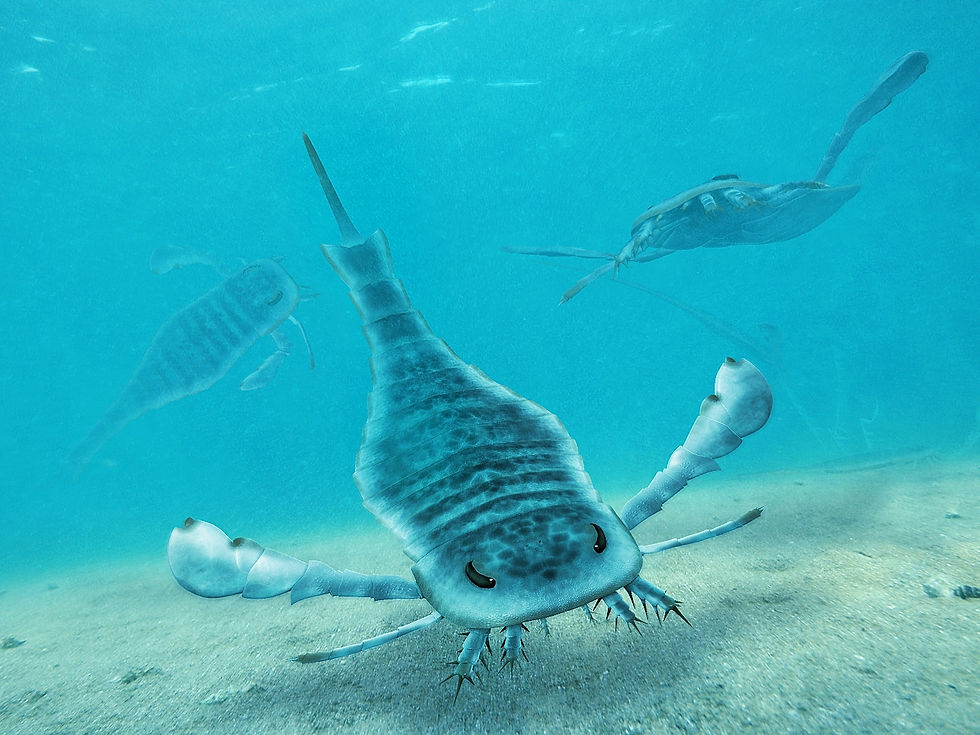

In 1887 George Matthew’s discovered a fossil of a Silurian pteraspid fish the first such find in North America. The Cunningham Creek Formation preserves both early vertebrates and invertebrates. Key fossil discoveries include the armoured heterostracan fish Cyathaspis, the thelodont Thelodus, the acanthodian Nerepisacanthus denisoni, and remains of anaspids ("shieldless ones") an extinct group of jawless fish alongside invertebrates such as the predatory eurypterid or Sea Scorpion known as Bunodella horrida, ostracods, and other small crustaceans. The Cunningham Creek Formation is significant for telling the story of the diversification of both jawless and jawed fish during the Silurian.

Tucker Park is located at the confluence of the Saint John and Kennebecasis Rivers in the Stonehammer UNESCO Global Geopark and its red sandstone of the Kennebecasis Formation dates to the Devonian Period over 375 million years ago. The Kennebecasis Formation was deposited by ancient rivers draining from the rising Appalachian Mountains.

These sediments, often cemented with pebbles and boulders to create distinctive landscapes such as the headland at Boars Head in Saint John. This period in New Brunswick was marked by intense mountain-building as the Rheic Ocean closed and the supercontinent of Pangaea formed. Erosion of the newly uplifted Appalachian ranges produced vast quantities of red, non-marine sediments, contributing to the characteristic “Old Red Sandstone” landscapes seen across the Maritimes of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island as well extending to parts of Europe.

Fossil discoveries include the Late Devonian Porolepiformes a lobe-finned fish known as Holoptychius. This was also a time of rapid evolution for bony fish, sharks and amphibians transitioning from water to the land. Invertebrate trace fossils, including the trace fossils of Protichnites, Diplichnites, Gordia, Helminthoidichnites and Gyrophyllites have been found in alluvial overbank and floodplain deposits representing some of the oldest continental ichnofossils from the base of Romer’s Gap.

Interestingly, this gap of 15 – 20 million-years was named after American palaeontologist Alfred Sherwood Romer (1894 – 1973) known for his concepts of evolutionary history of vertebrates. This time marked the transition from the Devonian into the Early Carboniferous and is uncharacteristically sparse of fossils showing how tetrapod's evolved from having paddle-like limbs to having pentadactyl or having having five digits on each limb that in-part enabled them to transition from an aquatic life to living on land.

The sedimentary rocks dating to the Lower Carboniferous at Stonehammer UNESCO Global Geopark include the Albert Formation that dates to the Early Mississippian Age between 358.9 - 323.2 million years ago. This formation holds Canada’s oldest known fossil forest located near the village of Norton on Highway 1 near mile marker 171 - no stopping is allowed.

This is a forest of over 700 fossilised lycopsids that once thrived on a floodplain of lakes, swamps and rivers. The forest is dominated by lycophytes such as Lepidodendropsis corrugata alongside other non-woody arborescent plants with unbranched trunks such as Sanfordiacaulis densifolia. This forest represent one of the earliest examples of how plants under a canopy evolved to grow by capturing uneven and obscured light.

The Upper Carboniferous rocks of Stonehammer UNESCO Global Geopark represent an ancient terrestrial ecosystems somewhat like Nova Scotia’s Joggins Fossil Cliffs. The Fern Ledges site in Saint John is within the Pennsylvanian Lancaster Formation that preserves one of the most diverse fossil assemblages from Late Westphalian A or Langsettian Age about 318 - 319 million years ago. Fern Ledges has played a key role in paleobotanical research since the 19th century, with pioneering studies by G.F. Matthew, Charles L. Hartt, and Marie Stopes establishing its scientific importance and confirming its Pennsylvanian age. Deposited on a tectonically active coastal plain, the formation shows braided rivers draining into a shallow brackish gulf with periodic flooding and abrupt subsidence creating ideal conditions for exceptional fossil preservation.

Fern Ledges preserves a remarkably diverse fossil assemblage including a range of plant groups, such as Laveineopteris, with species like Laveineopteris polymorpha well represented, alongside sphenopsids like Annularia and Asterophyllites, scale-leaved lycopsids, seed-bearing pteridosperms, and ferns related to modern Hymenophyllum, such as Zeilleria. The site also contains a rich invertebrate fauna including crustaceans, Eurypterids, gastropods, arachnids, insects, and myriapods, providing insight into the complex ecological communities of the time. Today locations like McPhersons Beach, Reeds Beach and Seaside Park allow visitors to explore the Upper Carboniferous.

The Permian-Triassic rocks along New Brunswick’s Bay of Fundy, including Saint John, St. Martins, Quaco, and the Fundy Trail Parkway mark the breakup of Pangea and the formation of the Atlantic Ocean. Composed of red sandstones and coarse boulder conglomerates dating from roughly 290 - 250 million years ago, these formations preserve the youngest Permian and earliest Triassic deposits in Atlantic Canada. Coastal erosion has sculpted dramatic sea caves, cliffs, and the Hopewell Rocks or “flowerpot” rocks.

The Permian-Triassic rocks along New Brunswick’s Bay of Fundy, including Saint John, St. Martins, Quaco, and the Fundy Trail Parkway mark the breakup of Pangea and the formation of the Atlantic Ocean. The red sandstones of the Honeycomb Point Formation and coarse boulder conglomerates of the Quaco Formation indicate an ancient rift valley of braided rivers and prograding alluvial fans triangular in shape extending outwards from higher ground. The distinctive red beds indicate an arid to semi-arid climate.

The Honeycomb Point Formation preserves primarily trace fossils of burrowing making it a Scoyenia ichnofacies reflecting a transition from terrestrial to non-marine aquatic environments, such as river channels and lake margins where sediments experienced periodic flooding and drying. Together, these trace fossils provide a window into Permian ecosystem shaped by alternating wet and dry conditions.

In more recent times the Quaco Formation has revealed fossilised tetrapod footprints at Quaco Head and after analysis by Columbia University now represent one of the rarest Late Permian fossil finds worldwide that predate the Permian–Triassic extinction event and the rise of dinosaurs. This find underwrites the critical role of citizen scientists in palaeontology and the importance of legally reporting fossils under New Brunswick’s Heritage Conservation Act, ensuring that Earth’s deep history is preserved within the Stonehammer Geopark.