Discover Germany and Explore the Fossils & Geodiversity of Bergstraße-Odenwald UNESCO Global Geopark

- Jan 12

- 6 min read

The Bergstrasse-Odenwald UNESCO Global Geopark, designated in 2015, is one of Germany’s most geologically diverse regions, preserving over 500 million years of Earth history. Located south of Frankfurt am Main between the Rhine, Main and Neckar rivers, it reveals striking contrasts between the Upper Rhine Plain and the Odenwald Mountains. Variscan crystalline basement rocks, Triassic sandstones and marine limestones, Ice Age landforms, and volcanic features tell a story of continental collision, rifting and climate change. Iconic sites such as the Felsenmeer boulder field and the Messel Pit UNESCO World Heritage Site provide exceptional insights into geology, fossils, landscapes and long-term human interaction, making the geopark a leading destination in Europe.

Designated as a UNESCO Global Geopark in 2015, the Bergstrasse-Odenwald UNESCO Global Geopark is one of Germany’s most geologically diverse and scientifically important landscapes. Located south of Frankfurt am Main between the Rhine, Main, and Neckar rivers, the geopark covers approximately 3,778 square kilometres and preserves an extraordinary archive of more than 500 million years of Earth history. Within this relatively compact region, dramatic contrasts unfold between the flat expanses of the Upper Rhine Plain and the deeply eroded uplands of the Odenwald Mountains, where geology, landscape evolution, ecosystems, and human history are inseparably intertwined.

The broad, low-lying Rhine Valley formed by tectonic subsidence and is associated with the Rhine Graben, while the steep mountain road of the Bergstraße marks the abrupt transition to the uplifted crystalline rocks of the Odenwald. Further east, the landscape opens into the gently rolling plateaus and deeply incised valleys of sandstone followed by the shell limestone hills of the Bauland, where karst features such as caves and sinkholes can be found.

At the heart of the Bergstrasse-Odenwald Geopark is an ancient mountain belt formed during the Variscan Orogeny in the Paleozoic Era. Between roughly 500 and 340 million years ago, continental collisions associated with the assembly of the supercontinent Pangea generated immense pressures deep within the Earth’s crust. Granites, diorites, gabbros, and metamorphic rocks crystallised several kilometres below the surface, forming the crystalline basement of the Odenwald. Later uplift and erosion gradually exposed these rocks.

Overlying this ancient basement are sedimentary successions from the Triassic Period, when the region lay at the margin of shifting continental interiors and shallow seas. The Bunter Sandstone is a prominent Lower Triassic rock formation in Germany and a key component of the Germanic Trias Supergroup, lying above the Permian Zechstein and beneath the Muschelkalk. Characterised by its distinctive red to greenish sandstones, the Buntsandstein was deposited in arid to semi-arid environments dominated by wind-blown dunes and ephemeral river systems. These iron-rich “red beds” form notable landscapes, including forested uplands and sandstone plateaus around the Black Forest, the Rhine region, and basins in Hesse and Thuringia. Fossil preservation is sparse due to harsh depositional conditions, but the Buntsandstein is internationally renowned for its trace fossils, especially the large Chirotherium footprints that document early Triassic terrestrial vertebrate activity.

The Muschelkalk (Shell Limestone) of the geopark is a classic Middle Triassic limestone succession that records the return of a warm, shallow sea to Central Europe around 240 million years ago. Deposited within the Southern Germanic Basin following a major marine transgression from the Tethys Sea, the Muschelkalk is sandwiched between the terrestrial Buntsandstein below and the more variable Keuper above. Its geology reflects repeated fluctuations in sea level and water chemistry, producing distinctive cyclic sequences of limestone, marl, and evaporites that are divided into the Lower, Middle, and Upper Muschelkalk spanning from the early to late Anisian Stage.

The Lower Muschelkalk is dominated by wavy-bedded limestones and porous oolitic “Schaumkalk,” formed during the early Anisian Stage of the Middle Triassic, approximately 247–245 million years ago. It records the initial marine transgression into the Germanic Basin, with shallow, high-energy carbonate deposition. In contrast, the Middle Muschelkalk spans the middle to late Anisian, roughly 245–243 million years ago. It reflects restricted, evaporitic conditions, with widespread deposition of gypsum, anhydrite, and halite during periods of reduced marine circulation. These rock salt deposits that remain economically important today. The Upper Muschelkalk dates to the late Anisian into the early Ladinian Stage, approximately 243–241 million years ago. This interval marks a return to more open-marine conditions and is characterised by fossil-rich thick crinoidal limestones called "Trochitenkalk" and marly interbeds. Many of these fossils that can be seen at the Muschelkalk Museum in Ingelfingen.

These rocks preserve abundant crinoids such as Encrinus liliiformis, along with bivalves, gastropods, brachiopods, sponges, corals, and diverse cephalopods, especially Ceratites, which are vital for Triassic biostratigraphy. The fossil assemblages here reveal a thriving marine ecosystem that existed long before the rise of dinosaurs, occasionally yielding remains of marine reptiles like Nothosaurus and Placodus. Beyond its paleontological importance, the Muschelkalk is significant for karstification, aquifer development, and its use as building stone. This limestone sequence tracks Triassic sea-level change, climate, and continental-scale processes across Central Europe.

One of the most striking features of the geopark is the Felsenmeer, or “Sea of Rocks,” in the Odenwald. This boulder field consists of thousands of massive blocks derived from granite-like crystalline rocks. These rocks were uplifted during Paleozoic mountain building and later fractured along joints. During the Quaternary Ice Ages, intense freeze-thaw cycles in periglacial conditions caused the rock to disintegrate and slowly flow downslope, creating the chaotic accumulation of boulders seen today.

The Felsenmeer is also a powerful example of human-Earth interaction. Between the second and fourth centuries AD, Roman stoneworkers exploited the durable granite for building projects across the region. More than fifteen Roman quarry workshops and approximately 300 unfinished or damaged stone blocks remain scattered across the site, frozen in time after quarrying activities ceased. Today, the Felsenmeer Information Centre allows visitors to explore both the geological processes that created the boulder field and the archaeological evidence of early industrial stone extraction.

While the Felsenmeer illustrates the effects of cold-climate processes on ancient crystalline rocks, the Messel Pit Fossil Site reveals an entirely different chapter of Earth history. Located near Darmstadt in the northern part of the geopark, Messel is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and widely regarded as the most important Eocene fossil locality in the world. Dating to approximately 47 million years ago, Messel preserves an exceptionally detailed snapshot of life during a warm, humid “paratropical” climate, when mammals were rapidly diversifying and establishing themselves in terrestrial ecosystems.

The Messel Pit originated as a volcanic maar formed during Cenozoic rifting associated with the development of the Rhine Graben. Faulting created subsiding basins that filled with freshwater lakes, surrounded by dense subtropical forests. Over time, thick accumulations of fine-grained sediments, including oil shales and lignite, settled on the lake floor. These sediments eventually reached depths of up to 190 metres and, crucially, were preserved from erosion due to continued subsidence along fault zones.

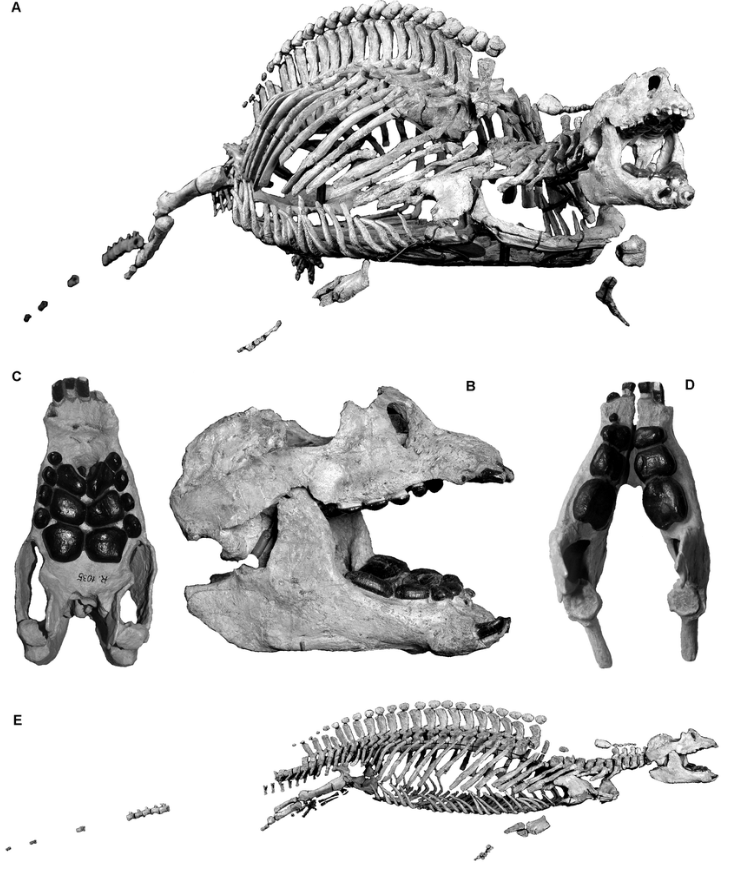

Unlike many fossil sites, which yield only fragmentary remains, Messel produces fully articulated skeletons of vertebrates, often preserving outlines of fur, feathers, and even stomach contents. More than 50,000 fossils have been documented, representing over 1,000 species, including more than 45 mammal species, around 50 bird species, over 80 insect species, and representatives from more than 100 plant families. Early horses such as Eohippus, primitive bats, pangolins, marsupials, crocodiles, fish, insects, and flowering plants together form a complete ecosystem frozen in time.

These fossils provide unique insight into the early evolution of mammals, including the origins of powered flight in bats and the ecological diversification that followed the extinction of the dinosaurs. Messel is particularly valuable for reconstructing behaviour and ecological interactions, as stomach contents reveal diets and trophic relationships, while entire skeletons allow detailed anatomical studies.

Beyond Messel and the Felsenmeer, the Bergstrasse-Odenwald Geopark preserves abundant evidence of Tertiary volcanism, river terrace formation, loess deposition, and landscape modification during the Ice Ages. Basalts and rhyolites indicate ancient eruptions linked to crustal stretching, while river gravels and wind-blown silts record repeated cycles of erosion and sedimentation during Quaternary climate fluctuations. These features show how tectonics and climate have continually reshaped the region.

The geopark describes its rocks as a “stone library of Earth’s history,” and this metaphor is apt. Each outcrop preserves information about ancient environments, global climate systems, and the shifting positions of continents over deep time. In combining world-class fossil sites, geological landscapes, and a deep record of human interaction with Earth resources, the Bergstrasse-Odenwald UNESCO Global Geopark stands as one of Europe’s most compelling deep time destinations.