Discover Canada and Explore the Fossils and Geodiversity of Miguasha National Park in Québec

- Sep 30, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Dec 19, 2025

Sip back and discover Canada and explore the southern shore of Québec’s Gaspé Peninsula at Chaleur Bay and Parc national de Miguasha that preserves the Escuminac Formation a Late Devonian formation that holds an exceptional assemblage of fish fossils and key evidence of the fish-to-tetrapod transition. Inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999, Miguasha exposes ~120 m of alternating sandstones, shales and mudstones deposited in a brackish estuarine setting where ripples, flute casts and turbidites rapidly buried organisms and enabled soft-tissue preservation. More than 18,000 specimens represent five major Devonian fish groups including placoderms, acanthodians, actinopterygians, sarcopterygians and jawless fishes plus the emblematic taxa of Eusthenopteron and the near-complete Elpistostege whose limb-like fins show the anatomical steps toward weight-bearing limbs and wrists. Complemented by plant spores and terrestrial arthropods, the assemblage reconstructs a coastal ecosystem during the “Age of Fishes.” Carefully managed excavations, an on-site museum and interpretive trails make Miguasha a must-see destination offering a story into the origins of terrestrial vertebrates.

On the rugged north east coast of Canada where the Gaspé Peninsula meets Chaleur Bay lies the Parc national de Miguasha (Miguasha National Park) in Québec one of the world’s most important fossil sites. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999 the cliffs of the small provincial park expose the Escuminac Formation from the Frasnian Stage between 385.3 - 374.5 million years ago during the Late Devonian. Known as the “Age of Fishes” the Devonian was a time of extraordinary biological innovation and the fossil record at Miguasha tells a story of the evolutionary transition of fish to land living tetrapod's. The scientific importance of Miguasha has been recognised for nearly two centuries. The site was first noted in 1842 by geologist Abraham Gesner, though its significance became clearer in 1892 with the discovery of Eusthenopteron. Since then, systematic excavations have revealed thousands of specimens with each new find adding to the evolutionary puzzle.

Miguasha sits within the Avignon Regional County Municipality near to the towns of Nouvelle and Escuminac. From its coastal cliffs, visitors look out across Chaleur Bay, a broad estuary at the mouth of the Restigouche River that separates Québec from New Brunswick. While today the setting is of a low-lying coastal landscape the region is deeply tied to the tectonic history of the Appalachian Mountains. The peninsula formed when the North American, African and European tectonic plates collided during the Paleozoic uplifting ancient seafloor sediments and creating the Gaspé Basin. During the Pleistocene glaciations, vast ice sheets scoured the terrain, leaving behind valleys, striated rock surfaces and a rebounding shoreline. As the glaciers retreated, the land rose through post-glacial isostatic adjustment or the vertical movement of the Earth's crust in response to the melting of ice sheets and glaciers has exposed these fossil bearing cliffs.

The Escuminac Formation reaches about 120 meters in thickness and is composed of alternating sandstones, shales and fine mudstones. Laid down in a brackish estuarine environment where tidal currents, fluctuating salinity, and frequent flooding created conditions ideal for fossil preservation. Sedimentary signature structures such as ripple marks, flute casts, and tool marks record indicate the currents and storms and turbidite deposits triggered by slope collapse or floods indicate times when fish were rapidly buried preserving their remains in exceptional detail.

The Escuminac Formation is described as a konservat-lagerstätte a rare type of fossil deposit where both hard and soft tissues are preserved. At Miguasha, fish skeletons remain articulated, scales retain microstructural detail, and in some cases internal organs have left impressions. This level of preservation places Miguasha in the company of other world-class fossil sites such as the Cambrian Burgess Shale of British Columbia, the Carboniferous Mazon Creek of Illinois and the Eocene Messel Shale of Germany.

Over 18,000 specimens have been collected from the cliffs with thousands more housed in Miguasha’s on-site Natural History Museum. Together, they represent an astonishing breadth of Devonian vertebrate life. Fossils from five of the six major fish groups of the period have been found here, including placoderms, acanthodians, actinopterygians (ray-finned fish), sarcopterygians (lobe-finned fish), and jawless fish. Only cartilaginous fish such as sharks are absent.

Among the most iconic discoveries at Miguasha is Eusthenopteron foordi, a lobe-finned sarcopterygian whose fins contain bony structures similar to tetrapod limbs. With its internal bone arrangement resembling primitive arms and legs Eusthenopteron has become a example for the fish-tetrapod transition.

Equally significant is Elpistostege watsoni, first described in the 1930s from partial remains but dramatically redefined in 2010 when a complete specimen was unearthed. This extraordinary fossil revealed digits within its fins and is thought to be clear evidence of the evolutionary steps toward the evolution of true tetrapod limbs. Dubbed “the missing link” Elpistostege confirms Miguasha’s role as a critical site for understanding vertebrates’ first ventures onto land.

Other notable fossils include Miguashaia bureaui, an early coelacanth and Bothriolepis canadensis, an armored placoderm. Together with lungfish such as Scaumenacia curta and small acanthodians like Triazeugacanthus affinis, these species illustrate the full diversity of Devonian fish life.

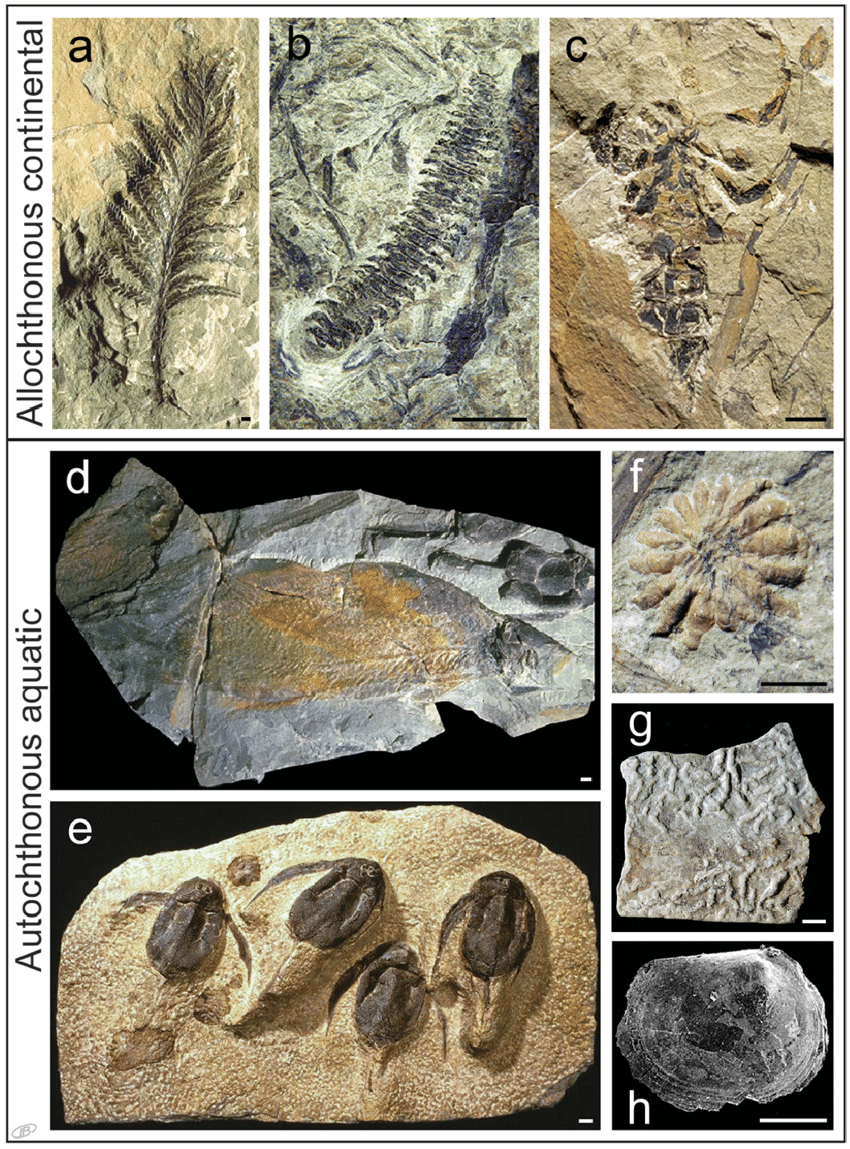

Beyond vertebrates the Escuminac Formation also preserves spores, plants, and terrestrial arthropods. The newly described flat-backed archipolypodan millipede Zanclodesmus willetti represents a new genus and species and documents the first North American record of the family Zanclodesmidae, confirming a geographic continuum of Devonian millipede fauna. Alongside this find, Miguasha preserves Petaloscorpio bureaui, an early terrestrial scorpion discovered in 1964, plus rare fragments of large aquatic eurypterids (water scorpions) together expanding our picture of Devonian arthropod diversity.

A) Archaeopteris halliana, B) Zanclodesmus willetti, C) Petaloscorpio bureaui, D) Bothriolepis canadensis (two specimens) and Scaumenacia curta (two large specimens), E) Bothriolepis canadensis, F) Gyrophyllites, G) Planolites montanus, H) Asmusia membranacea

The millipede and scorpion fossils are pivotal for palaeontology because they document early colonisation of land by arthropods. The co-occurrence of marine, brackish and terrestrial fossils makes Miguasha a unique window into entire ecosystem.

The transition from water to land is one of the most profound events in the history of life. Fossils from Miguasha document the anatomical innovations that made this leap possible. The sarcopterygian fins of fishes like Eusthenopteron and Elpistostege contained bones that evolved into weight-bearing limbs, complete with wrist-like joints. Meanwhile, the transformation of the swim bladder into lungs allowed air-breathing, while internal nostrils or choanae provided a new way to breath. These anatomical adaptations bridged aquatic and terrestrial life and laid the foundation for tetrapod's to go on to colonise terrestrial environments, giving rise to amphibians, reptiles, mammals and ultimately humans.

Miguasha National Park in Québec's Gaspé Peninsula offers the visitor a rare, accessible window into the Devonian "Age of Fishes," where exceptional estuarine-sediment fossils along Chaleur Bay record the water-to-land transition. The park’s interpretive trails, guided fossil-cliff tours and the immersive “From Water to Land” exhibit and home to the world’s only complete Elpistostege specimen. Set against the dramatic Chic-Choc Mountains and enigmatic Percé Rock, Miguasha blends geoheritage, geology and wildlife into a compelling destination.